Karakia Tīmatanga

E te Atua

Arahina ngā kōrero

Arahina ngā pātai

Arahina ngā ture nei

Kia puta ai te marama

Amene

Dear Lord

Guide our words and speeches

Guide our questions

Keep true our respect amongst us

To let knowledge emerge

Amen

Exploring te ao Māori Through Picture Books

By Anne Coppell

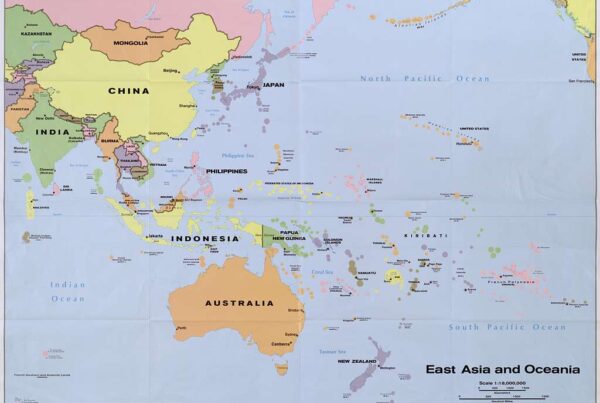

February 6 is Waitangi Day in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

It commemorates the first signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi / The Treaty of Waitangi.

For those looking in, race and indigenous relations can seem paradisal in Aotearoa.

It can seem that way to many here, too. Well, to many pākehā (New Zealand Europeans). For Māori – the story is not so rosy.

As you can tell by my mihi to the side, I am not Māori.

But, I can try and offer others a glimpse into te Ao Māori.

I do this with a background as the ‘white chick’ (my words) in training groups. The one who tries to understand the Kaupapa or wairua of something and ‘translate’ it into something helpful — not harmful — for non-Māori to use in their storytime sessions.

I realise that many of these books may be hard to come by, if you’re not in New Zealand – but I wanted to share some taonga with you.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi / Treaty of Waitangi was a written agreement made in 1840 between the British Crown (the monarch) and more than 500 Māori chiefs. After that, New Zealand became a colony of Britain and Māori became British subjects. However, Māori and Europeans had different understandings and expectations of the treaty.

~ From Te Ara (online encyclopedia).

You can find a brief history of the Māori peoples in Te Ara encyclopedia. But, to give you something to start with…

Māori are the indigenous people of Aotearoa, New Zealand. They arrived around 1250-1300 CE.

They came from Hawaiki — a place that has not been pinned down. But its significance as the origin — the homeland — cannot be understated.

E iti noa ana, nā te aroha.

Although it is small, it is given with love.

There is a glossary of words and phrases at the bottom of the page. Where possible, I have included pop-up definitions within the text, with more explanation (if needed) in the glossary.

It is tikanga to begin with a mihi including a brief whakapapa – as I have below.

Ngā mihi Lawren, for pre-reading and checking this post.

Tēnā koutou katoa

(Hello to all)

E mihi ana ki ngā mana whenua

(Greetings to the indigenous people of the land)

Nō Airangi me Ingarangi ōku tīpuna

(My ancestors came from Ireland and England)

I tipu ake ahau ki Opanuku

(I grew up in Henderson, Auckland)

Ko Anne tōku ingoa

(My name is Anne)

E mahi ana ahau hei poukōkiri

(I work as a Senior Librarian, Children and Youth – the children and youth bit isn’t in the te reo Māori title)

Ki te Pātaka Kōrero o Awaroa

(At Helensville Library)

Nō reira, tēnā koutou katoa

(Once again, hello to you all)

A pepeha is a way of showing your connections to your whakapapa – including your ancestral connections to the natural environment.

Six60, a New Zealand band, created this song to connect everyone.

Te reo Māori and NZSL are the two official languages of Aotearoa New Zealand (English is a common use language.)

Retold by Kāterina Mataira, illustrated by Claire Bowes

Published in 1975, this book was a mainstay in many a home and school. Dame Kāterina Te Heikōkō Mataira was fundamental to the revitalization of te reo Māori, including the growth of Kura Kaupapa Māori.

Composed by early members of Te Ataarangi in honour of Kāterina Mataira and the kaupapa of Te Ataarangi. It describes how a single person or kaupapa can have a great impact, just like a single raincloud on parched crops.

Kotahi kapua ki te rangi

He marangai ki te whenua

Ki te whenua.

Just one cloud in the sky can give

a lifegiving shower of rain on the land,

on the land.

Kotahi kapua ki te rangi

He marangai ki te whenua

Ki te whenua.

Just one cloud in the sky can give

a lifegiving shower of rain on the land,

on the land.

Kua whiti te rā

Ki tua o Kahurangi

The sun has shone

all over the blue sky

Kia kore koe e ngaro

Taku reo rangatira.

So that you will not be lost

My chiefly language

Translation from: folksong.org.nz

Audio from Anne’s te reo Māori class, run using Te Ataarangi principles.

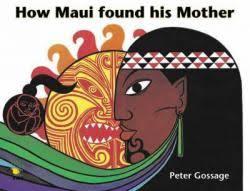

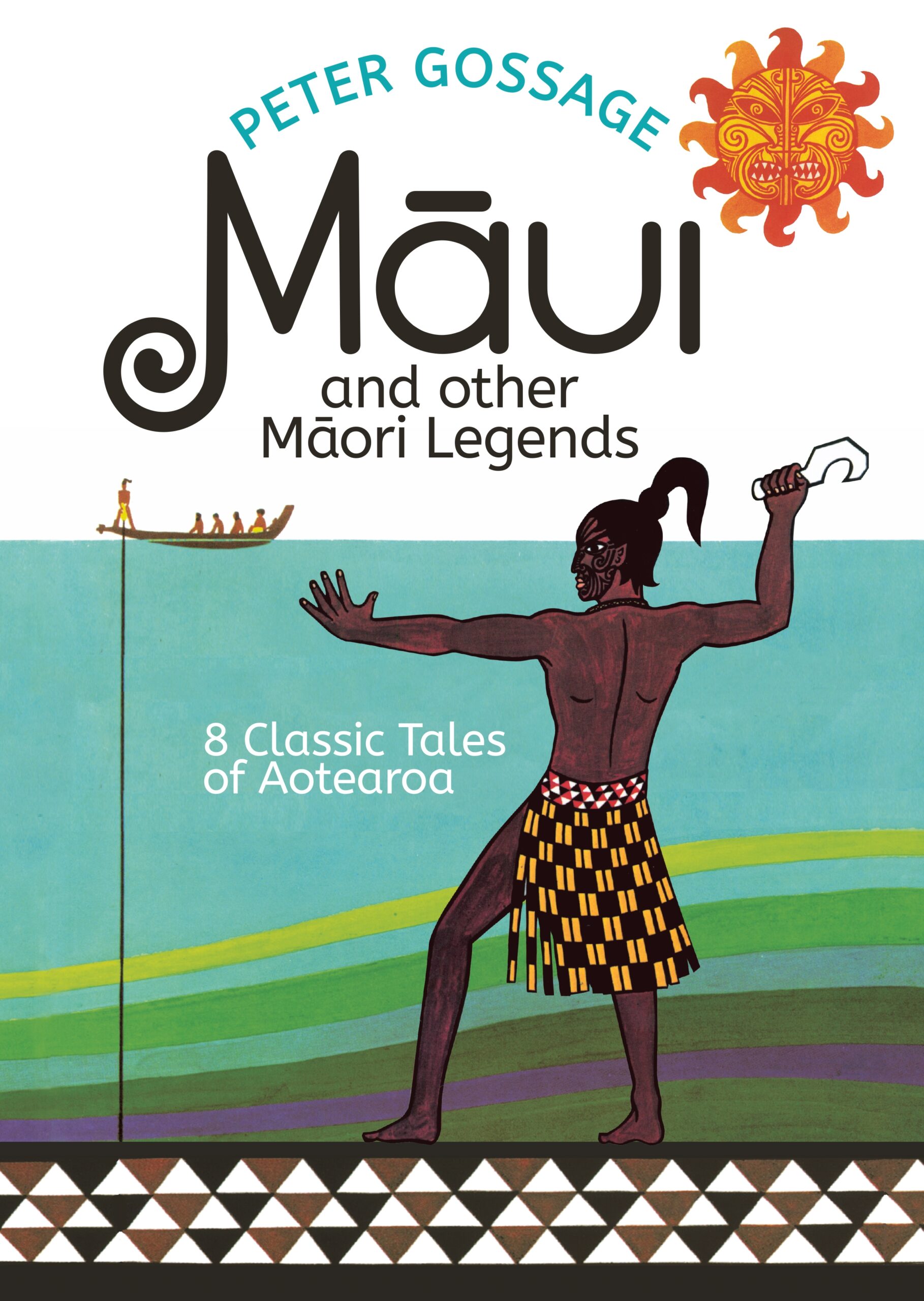

By Peter Gossage

Originally published as ‘How Maui-tiki-tiki-a-Taranga Found His Mother’ in 1975, Peter Gossage went on to have a heralded career in publishing. It was through his work that many non-Māori came to know Māori legends.

Peter Gossage

In the 70s, very few local picture books were available; Peter was one of the first to try and to succeed. “His books played a unique and critical role in reflecting stories and legends of Aotearoa for young people,” says Elizabeth Jones of the National Library. She believes they “had an enormous impact in raising awareness and understanding in schools at a time when there was not all that much published. And they were visually wonderful.”

John Huria, senior editor at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, sees the books as a gateway for many children “to the Māori visual interpretation of the stories of Aotearoa.”

~ From Rhymes with Sausage: A tribute to Peter Gossage, by Paula Morris.

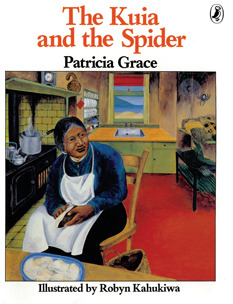

by Patricia Grace; illustrated by Robyn Kahukiwa

These two wāhine toa teamed up to create two classics of New Zealand’s publishing, this, and ‘Watercress Tuna and the Children of Champion Street.’ Together, or separately, they are worth checking out. And, ‘The Kuia and the Spider’ is a great readers theatre!

How do you pronounce te reo Māori?

Many of us learnt through waiata – particularly A Ha Ka Na. I was so pleased when I found this video, as it was slower than most versions!

Waiata Māori for kids – Te Wiki o te Reo Māori 2021.

Filmed during lockdown in August 2021, by kaiako Gabriel Tongaawhikau from within his bubble.

Credit: Auckland War Memorial Museum.

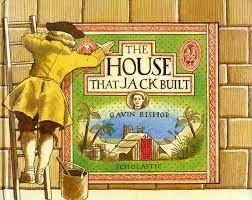

Gavin Bishop

The House that Jack Built

Originally published in 1999, although this features no te reo Māori in the text (being a traditional English rhyme), the illustrations are a tour de force in imagining the colonization of New Zealand. It is stunning, end paper to end paper.

You can see examples of the artwork from the publisher’s website.

Weaving Earth and Sky: Myths & Legends Of Aotearoa

Written by poet (and librarian!) Robert Sullivan, this collection of legends was published in 2002.

Written for an older audience, this is a powerful read aloud.

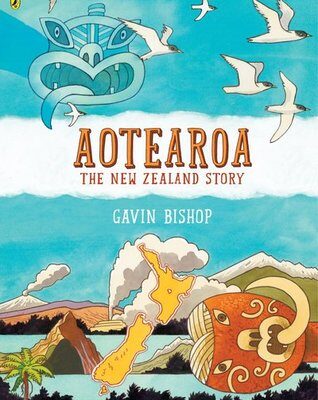

Aotearoa: The New Zealand Story

Published in 2017, this large format non-fiction is a joy.

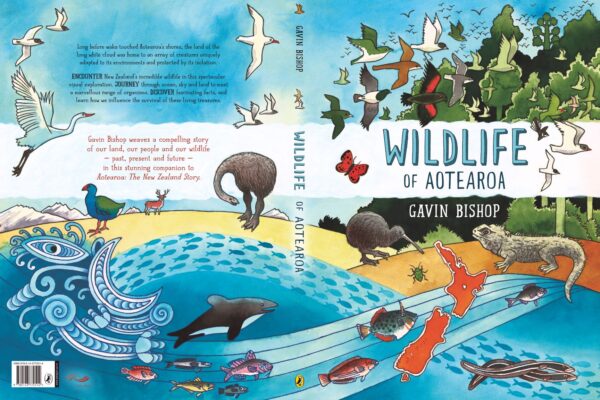

Read alongside his ‘Wildlife of Aotearoa‘ (published 2019).

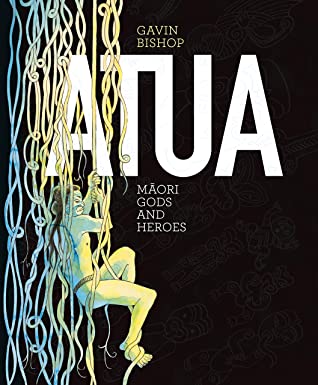

Atua: Māori Gods and Heroes

Published in 2021, I *had* to buy this for myself with my birthday money from my mum.

Before the beginning there was nothing.

No sound, no air, no colour – nothing.

TE KORE, NOTHING.

No one knows how long this nothing lasted because there was no time.

However, in this great nothing there was a sense of waiting.

Something was about to happen.

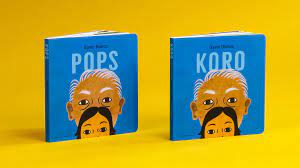

Koro / Pops

Published simultaneously in te reo Māori and English editions – this simple board book is a joy to hold, and behold.

Gavin Bishop O.N.Z.M

Ngati Pukeko, Ngati Awa, Ngati Mahuta, Tainui

written by Melanie Drewery; illustrations by Tracy Duncan

The first Nanny Mihi book, ‘Nanny Mihi and the rainbow‘, was published in 2001. This title was published in 2004. I rejoice in the fact there is no glossary – we are expected to understand te reo Māori kupu.

Written and illustrated by Robyn Kahukiwa

This self-published rhyming picture book is definitely for older readers. The author does *not* pull any punches.

I think that the self-publication route has allowed creators to be more political – to not tone down their message, in order to be published.

If you are looking for a Māori perspective on James Cook’s ‘discovery’ of Aotearoa…

Now Cook and his crew had guns they could fire

But not so the Māori and this became dire

When Cook shot nine Māori,

They fell dead in the sand

Just ‘cos the king wanted new lands

By Darryn Joseph; illustrated by Munro Te Whata

From the publishers website:

One night in June 2016, Massey University language lecturer Darryn Joseph sat in a hospital room minding a teacher who had become a dear friend and mentor to him. Darryn wrote her a poem of appreciation, kissed her hand and said goodbye; the next day she passed away.

That poem is contained in ‘Whakarongo ki ō Tūpuna/Listen to your Ancestors,’ which is written in te Reo Māori with English translation.

The story follows a beloved teacher giving her pupils and granddaughter guidance by directing them to follow the examples of Māori gods and ancestors.

The book is illustrated by emerging artist Munro Te Whata, who has vividly brought to life settings in a school, the outdoors and a rest home in a colourful and fun style.

‘Whakarongo ki ō Tūpuna’ teaches the values represented by Māori gods and ancestors, and provides a much-needed tool for reading in te Reo. And at its heart this is a story of love and respect, harking back to the friendship that inspired its writing.

There is an excellent video interview with the author, discussing te reo Māori in publishing. (I highly recommend this course, too.)

Kupu Hou (New words)

Many of the words and phrases used here have many definitions. You can search for other definitions on Te Aka Maōri Dictionary.

Usage and understanding of kupu can be highly charged – emotionally and politically. In Aotearoa, New Zealand, many kupu are used as part of everyday discourse. But, even saying Aotearoa as your preferred name comes with backlash.

As with any item of cultural significance – tread carefully and respectfully.

- te Ao Maōri: the Maōri world.

- te reo Maōri: the Māori language.

- Pākehā: a New Zealander of (usually) English / British descent.

- Mihimihi: introductory speeches at the beginning of a gathering. Similar to a pepeha (below) but generally shorter, and not as formal.

- Pepeha: an introductory ‘speech’ based on your whakapapa (lineage).

- Kaupapa: purpose / theme.

- Wairua: spirit / soul.

- Taonga: treasure.

- Kura Kaupapa Māori: Māori language immersion school, at primary / elementary level.

- Wāhine: women.

- Toa: strong / brave / accomplished.

- Kuia: elderly woman, often used for grandmother.

- Kaiako: teacher.

Kia ora: most often translated as ‘informal greeting’. But, it is so much more than that. ‘Kia’ is an imperative – kia kaha = be strong / kia tupato = be careful. Therefore, ‘kia ora’ is ‘be well’. (It is also used as an acknowledgement when someone has spoken. It’s all in the tone as to whether it is approval, or otherwise.)

I have begun this article with a Karakia Tīmatanga – an opening prayer. In te ao Māori this is how each hui (meeting) or gathering starts. It sets the tone, and changes all the participants into a tapu (sacred) space.

We end with a Karakia Whakamutanga – a closing prayer. This puts participants back into noa (normal) space.

When exploring te ao Māori it is only tika (correct) that we follow tikanga Māori (protocols).

Kia ora.

What do you already know about Māori / New Zealand?

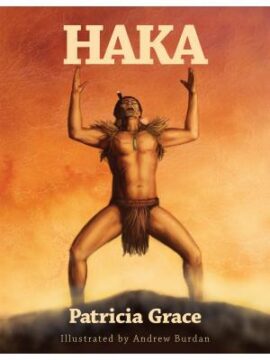

If anything, it would be the haka – the (erroneously called) ‘war dance’ – famously performed by the All Blacks (the New Zealand men’s rugby team) before test matches.

The one most commonly performed is “Ka Mate”. “Ka Mate” was composed by Ngati Toa Chieftain Te Rauparaha around 1820.

Patricia Grace has written about the origin of “Ka Mate” in ‘Haka‘.

Haka is more than that – far more meaningful than most realise.

Every action means something.

Every haka means something.

There is no one haka.

Haka is an expression of the performers’ wairua (spirit / life force). Sometimes – as in the haka before a sporting test (or a battle) – it is to imbue your wairua, your being, with the wairua of others. Be they your tūpuna (ancestors), Papatuanuku (Mother Earth), your group.

It is a way to test the courage of your opposites.

It is a way of honouring them. Only the worthy are gifted a haka. It is a challenge: do you have mana (authority / power) to stand up to ours.

It is an expression of passion, of your mana – and theirs.

It can be as an acknowledgement of manuhiri (guests); to honour great achievements; or at occasions when the wairua moves them – and the recipient’s mana deserves it. At funerals. At weddings.

Although ‘Ka mate’ is the most well-known haka, I wanted to share a few that draw from the deeper well.

The Black Ferns are Aotearoa / New Zealand’s women’s rugby team. ‘Ko Uhia Mai’ (‘Let It Be Known’) was written for them.

This video is subtitled, which helps in understanding the mana of the team, and the haka.

Staying on rugby, this is the haka performed by members of the Hawkes Bay rugby team, for their retiring captain, Ash Dixon. You can see from his emotional response what it means to him. He has to respond, with part of a haka, himself.

Haera rā means farewell.

After the haka, you see Ash hongi his teammates. Hongi can be referred to as ‘pressing noses’.

It is a greeting – it is an exchange of the breath of life, and comes from the way the god Tāne breathed life into Hineahuone, the first woman.

And, finally, the respect – and grief – shown by Palmerston North Boys High School, in the all-school haka performed when the hearse of a teacher arrived for his funeral.

Karakia whakamutunga

Unuhia, unuhia

unuhia ki te uru tapu nui

kia wātea, kia māmā, te ngākau

te tinana, me te wairua i te ara takatū

Koia rā e Rongo

whakairihia ake ki runga

Kia tina! TINA!

Haumi e, hui e! TĀIKI E!

Release, release

release us from this sacred state

to clear and set free the heart

body and spirit so that we are prepared

Let peace and humility

be raised among us

and be made manifest (indeed!)

Draw it together! Affirm! It is done!